The festival which came to stay!

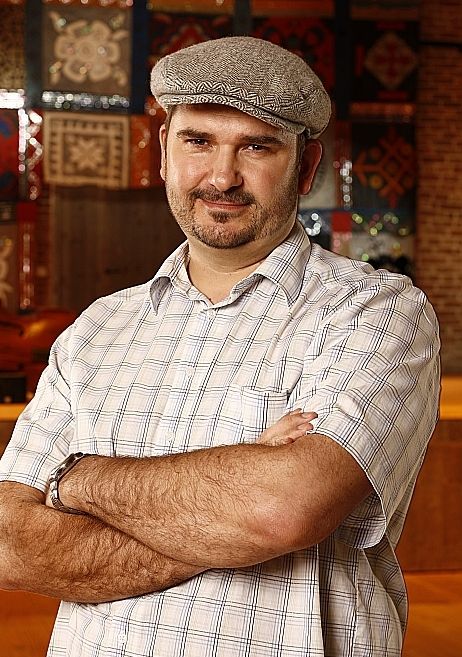

Ando Kiviberg, Head of the Festival

If you want to hear how Viljandi Folk Music Festival came to be, you have to go back in time.

If you want to hear how Viljandi Folk Music Festival came to be, you have to go back in time.

In 1989, the folk instrument programme led by Ene Lukka was launched at Viljandi School of Culture (nowadays known as UT Viljandi Culture Academy). The aim of the course was to train conductors for village bands and folk instrument orchestras. It was a tumultuous time in the School of Culture and in the society generally – Estonia had taken decisive steps towards freedom and the school had applied for the status of an institution of higher education.

In 1989, a new class of students were admitted for different 4-year courses at the Viljandi School of Culture with the promise of graduating with a degree in higher education even though the institution which could provide that had not been formed yet. The preparations for this were, however, well under way. The curricula had been restructured and the people were enthusiastic about offering a new level of quality.

The folk instrument department was immediately faced with a task of finding a new identity. On the backdrop of a quickly changing political situation, they had to find a way of breaking out from the Soviet pseudo folk art scene to offer a quality education in traditional music. The head of the programme, Ene Lukka looked abroad for help. The political situation had loosened up a bit and travelling to Finland was no longer the utopian dream it had been a few years ago. Anneli Kont, who was a former member of the folk band Leigarid and had graduated from Tallinn National Conservatory, was studying on a traditional music course at Sibelius Academy in Helsinki. Having heard about the developments in Viljandi, she hurried back home to help which meant that unprecedentedly exciting times were ahead for the newly-formed Viljandi Culture College. The students and lecturers from Sibelius Academy became frequent guests in Viljandi. The traditional instrument course was turned into a traditional music department following the example of Finland and new students were admitted. In addition to many others, Ando Kiviberg, Piret Aus, Ülle Jantson, Liina Kanemägi, Tuuli Peters and Raivo Sildoja „landed“ at the traditional music department.

Music was learned mainly based on hearing because understanding the peculiarities of different playing styles is incredibly important in traditional music and these can only be learnt by precise imitation. One completely new and exciting addition to the curriculum was the notation class which was similar to writing a melodic dictation in a solfeggio class. The only difference was that the music was not performed on the piano but played from an archival recording. These were recordings of village musicians from the beginning of the XX century. The lousy sound quality of these wax cylinders meant that the students had to concentrate hard in order to understand what was being played. In addition to the melody, they also had to write down all the variations, fluctuations in rhythm and pitch and also the so-called mistakes the musicians made.

This was the time when I fell in love with the bagpipe. I saw and heard bagpipes being played in a way I had never heard before. Among other guests from Sibelius Academy, the Finnish Swede Kurt Lindbladt who played in the bands Korkkijalga and Ottopasuuna came to visit us. He had chosen to research Estonian bagpipe for his Master’s thesis and he had learnt to play it with incredible charm and style based on old archival recordings. His playing skills gave me a boost which I can still feel to this very day.

Inspired by the atmosphere of new ideas, me and my course mates decided to start making music. We formed the band Alle-aa which in the year 1991 consisted of 14 people, including Piret Aus, Ülle Jantson, Raivo Sildoja, Margus Põldsepp, Ott Kaasik, Liina Kanemägi, Peep Harju, Tuuli Peters, myself and many others. Ene Lukka had the marvellous idea of going on tour with the band to introduce the new approach to traditional music and promote traditional culture in Estonian schools. We went to several educational institutions in Viljandi, Pärnu and Saaremaa counties. In Tori, we met Ants Johanson, who proposed that we should take part in the Falun festival in Sweden next summer. The Falun Folkmusik Festival, Svenska Rikskonserter and Jeunesses Musicales were organising an international young traditional musicians’ camp ETHNO which was held right before the summer festival. Ants had attended the camp with Jaak Tuksam, Jaan Sööt and Marko Matvere and he thought that Alle-aa would be perfect for representing Estonia at the event. An extremely busy period of organising followed, because in 1991, the Soviet Union with its strict border regime was still very much a reality. We needed to get foreign passports, Swedish visas, export documents for our instruments and find money fort travelling.

We asked the local carpenter to carve a suitcase for the contrabass which we had respectfully nicknamed „mother-in-law“ and which belonged to the Culture College. It looked like a coffin and created a lot of problems on the border. When we were carrying the instrument to the ferry across the harbour parking lot, Margus Põldsepp told everyone who went past that we are taking our dead granduncle home to Sweden to rest in peace in his home soil. He thought it was an ingenious joke at the time.

We had prepared for the trip following what was thought appropriate for a prim and proper traditional music group from the Soviet Union. All of us had brought a buttoned-up set of national dress and numerous gifts ranging from vinyl records to handicraft. As a group of stubborn nationalists, we could not go abroad without a fancy blue-black-white tricolor with an exceptionally vain pole. In addition to a contrabass and two accordions, we had an average of 2.5 musical instruments per person which we had to carry ourselves. You can only imagine what the Swedes, Germans, Danes and Flemish people thought when we arrived at Falun with an endless row of instruments and suitcases. They had come to a cosy summer camp, bringing only comfortable clothing, a musical instrument (usually a violin) and a sleeping bag. We, in turn, looked like a weird cocktail made of a folk group, itinerant salesmen and nationalist revolutionaries.

The Falun ETHNO camp was a shock for us in a positive way because it completely changed our understanding of the essence and meaning of traditional music in the contemporary society. Up until now, we had been taught to play songs „as they had been played before“, to think of them as musical museum pieces. In Falun, we were exposed to a completely different way of thinking. We saw living tradition. We saw young people who played old songs just because they enjoyed the sound of them. We saw youngsters who found a place after their daily lessons to play together with friends or alone just for the sake of it. They played the same old and ancient songs but added their own contemporary twists. The musicians did not care about having an audience, their goal was not to perform but to enjoy making music. It seemed that Sweden was fluent in its own musical mother tongue. It was viable, constantly developing and unique. We realised that traditional music is not simply something ancient and stagnant, it can be a natural part of contemporary life. We thought that we had found a method for creating this type of thinking. As all learning is based on living and infectious role models, we started looking for the best way to create these role models.

In the 1990s, the civil society was developing again in Estonia. The air was ripe with enthusiasm and fresh ideas. Old organisations were revived and new ones were created. The traditional music students at Viljandi Culture College realised that they need to group up to make their ideas a reality. We started creating the statute for the Noorte Moosekantide Selts (Young Musicians’ Society) which stipulated that the organisation is open to all active musicians under the age of 30. The aim of the society was to teach and promote living traditional music aka folk music. In addition to the traditional music students, Anzori Barkalaja, who was studying at the University of Tartu at the time, Raido Koppel and Mati Kiviselg from Väikeste Lõõtspillide Ühing and several others joined us.

While launching the organisation, we also started to think of other activities we could organise. At first, we had two ideas in mind – a festival and a children’s camp. The festival was to take place in Viljandi and the camp could be held in some other naturally beautiful place, preferably by the sea.

Organising a festival was a tremendously huge challenge because we had no experience in organising mass events and we did not have the faintest idea about compiling a budget or finding financial sources. Despite all that, we boldly got on with it. It did not take us long to realise that we needed experience, advice and help and we got very lucky. Young cultural entrepreneurs and the founders of Mulgi Fair Tiit Kalmet and Toomas Märamürk were based at Viljandi Culture Center. We turned to them for help in organising. We set a goal to hold a concert at the Christmas Fair of 1992 which was traditionally held at Viljandi Culture Center.

At the same time, I was preparing to welcome my daughter Anna Maria into the world, so organising the concert was delayed. The new date was set to be the 15th of May 1993 which coincided with the birth of the Young Musicians’ Society.

It would have been impossible to cover the budget for the festival if Toomas and Tiit had not helped us. It is important to point out that the first Folk Music Festival was organised solely on private funds. If it had not been for those generous sponsors, the festival might not exist in its current format.

The question of the name was a bone of contention. We did not want to use the word traditional music in the name. We wanted to boldly say that everything is different now in the world of traditional music. Ants Johanson reminded me that the group Kukerpillid used the word “pärimus” which means “folk” on their albums which is why we decided to use that to refer to the new type of folk music.

The term “pärimusmuusika” was precise and clear but unfortunately a bit too long. That was at least our impression at the time. The guitarist from the band Ummamuudu and our good friend Sulev Salm thought that shortening it to “pärimusa” would be a good idea. The young men felt it was fashionable and youthful enough so we used that term even though it did not feel quite right.

The line-up for the first festival consisted of Väikeste Lõõtspillide Ühing, Untsakad (known as Rahvastepall at the time), Tiit Kikas and Peeter Rebane, Justament and of course Alle-aa which had downsized from being basically an orchestra to only five members. The American-Estonian bagpipe and zither player Ain Haas added an international dimension to the event.

The Young Musicians’ Society was founded and the board members were appointed on the same day as Pärimusa. The director of the society was Raivo Sildoja, I was the treasurer and Ülle Jantson was the secretary. On May 15, around 200 ticket-buying guests sat at Viljandi Singing Grounds. It was not the greatest turnout but it was enough to give us courage to carry on. We realised that the idea to organise a large traditional music event was good enough to be more widely communicated. The first festival ended with a cosy jam at Viljandi Culture Center and I as the Head of Festival had to accommodate the few musicians who took part in my own home.

In addition to the board members, Marek Rätsep and Vahur Roht were also present at the birth of the Folk Music Festival. The latter possessed a lot of valuable know-how because he was the frontrunner of the legendary band Rock Ramp. Several other great people helped out us as much as they could as well.

After having acquired our first experiences as festival organisers, our plans became a lot more ambitious. I made it clear to my friends that we have to make friends with the national media channels, extend the festival to two days and create more stages.

The festival needed an international name because we realised that it needed to appeal to people beyond the Estonian borders. Following the example of similar events held in Falun and Kaustis, we decided to go with Viljandi Folk Music Festival. The popular Estonian nickname of the festival “Viljandi Folk” is derived from the English name.

The following winter was spent on looking for international performers, writing finance applications, talking to potential sponsors and enticing media channels. It was one meeting after another. Me, Raivo Sildoja and Marek Rätsep went to most of the newspaper offices, radio and TV stations. We also visited several companies and met with politicians. At the time, no one in Estonia knew anything about the internet or mobile phones. The only working fax machine in the Culture College was kept in the rector’s office which meant that after hours it became the office of the folk music festival. Me, Raivo Sildoja and Ülle Jantson dealt with all the paperwork and signed agreements. We were also graduating from the university at the time and writing our thesis. Looking back at it now, I have no idea how we managed to find time for both.

This is a good time to point out a quote from a letter I sent to Priit Hõbemägi, who was the editor-in-chief of Eesti Ekspress, on April 22, 1994. “By supporting us, you help to build a foundation to a magnificent summer tradition. Its fame will soon extend way beyond the Estonian borders.” This excerpt reflects how enthusiastic and fanatic we were about the road we had chosen.

The ideas which Mark Rätsep gathered from Eesti Elava Muusika Konverents (Estonian Live Music Conference), which was organised by Makarov Muusik, helped to significantly improve the quality of the festival. I also want to point out that several technical solutions created by Marek and Vahur Roht, who is a good friend of the festival, are used at the festival to this very day.

From the point of view of longevity, convincing the editorial team of the weekly newspaper Eesti Ekspress to help us was an incredibly important step. I cannot say it was easy – I was sent home from their office empty handed many times but I never gave up. In the end, we managed to get a free quarter-page black and white ad published thrice in their newspaper. This was a very big deal at the time! I believe that the decision by Priit Hõbemägi and Hans H. Luik to support an unknown event helped to tip the scales for several other supporters and created a fertile ground for the new event to grow into a big mass festival.

Kuku radio followed the example of Eesti Ekspress and thanks to the gentlemen Erki Berends and Rein Lang, they have remained loyal to us until this day. Let us not forget that from Tallinn or Tartu, Viljandi seemed like a total periphery where nothing noteworthy happened and organising an event there was seen as pure insanity.

While putting together the budget for the festival, we had to make sure that all the concerts were free. This would give the audience the opportunity to let themselves be convinced of the quality of the event without taking risks. By that time, several great big Estonian music events like Pärnu Fiesta and Tartu Music Days had seized to exist and the foundation of Rock Summer was crumbling fast. Due to economic hardships, people were very picky about everything that required a ticket. We also had to solve a very important problem – our baby had a name but it did not have a look. Tiiu Männiste who knew the Viljandi art scene well, suggested we turned to Tõnu Kukk for help in creating a design and finding a logo for the festival. We picked our final one out of several designs and it was used for several years.

Tiiu Männiste helped us a lot as an older colleague and seasoned events organiser. For example, she and other artists from Viljandi helped to create the stage behind the former Kilpkonna gallery on Tallinn Street which is also known as Tortila Yard.

And then it happened. After the 1994 Viljandi Folk Music Festival which took place on July 22-24, the daily newspaper Postimees announced in a heading, „Three days which shook the world.“ We succeeded in highlighting the cosiness of Viljandi and its beautiful environment to create a perfect place for enjoying music. We managed to create an atmosphere which elevated the musical experiences. As expected, numerous spontaneous jam sessions sprung up and both the audience and the journalists loved it.

The other new addition was workshops where foreign performers shared their music knowledge. Experiences gathered in such an intimate atmosphere were greatly valued by people. It is worth mentioning that the international festival line-up for 1994 included Prosper (Ireland-Finland), Snackorna (Sweden), Sutaras (Lithuania), Gullfakse&Heidi L (Norway), Stefan Timmermans&Friends (Belgium-Flanders) and Ruumen (Finland).

Viljandi Folk Music Festival was here to stay. In July 1994, it became clear that it will be an event which will bring together people and tradition.

The names of several incredibly helpful people have unfortunately been erased from my memory and the official volunteer lists includes names like “John’s brother’s friend”. There are some, however, who I will never forget. I mentioned Marek Rätsep’s, Ülle Jantson’s and Raivo Sildoja’s contribution already. Aleksander “Sass” Sünter was helping out in the transportation team together with his brother and his cars, Janno “John” Jaanus, Raini Kukk and Mehis Müürsepp. Inga Lill was the press secretary and Piret Räni helped to design the passes and other publications. Several other artists from Viljandi lend us a helping hand as well. The snippets of advice from Ants Johanson and Sulev Salm were always useful. Marek’s wife Lembe and Asser Ellermaa helped to keep an eye on the sales. Arno Jürjens is one of the founding fathers of the legendary Õlleõu. There were helpers everywhere. I apologise for everyone whose names I have not mentioned but I owe you all a lot. You were all essential to the success of these memorable days!

The main core of the organisers had received the coveted university degrees a month before the 1994 festival and we had fierce competition waiting for us at the job market. Raivo and I had hoped, based on certain promises which had been made, to become employed as lecturers at the Culture College. We had given lectures already as students and by the time we graduated, there were four younger year groups in the building. Unfortunately, we were both offered a quarter of a full-time equivalent and that was not enough to feed the family. Raivo was soon offered a job at Viljandi City Council and I walked into my teacher Katrin Mändmaa’s office. She had become the head of the education and culture department at Viljandi City Council. Astonishingly, she had a vacancy and offered me a job! I was of course quite baffled by all of this. I was going to be a manager of a cinema! Reads like a film script, does it not? Straight after the famous Viljandi Folk Music Festival in 1994, I started working as a manager of the Viljandi City Municipal Organisation “Rubiin”. It is probably clear to everyone that this became an important influence on the development of the festival in the coming years.

The feedback from the second festival was extremely positive from friends and the press alike. This spurred our ambitions even more. We decided that the festival will become a 4-day event the next year.

The 1995 Folk Music Festival confirmed without a shadow of doubt that it was here to stay. We decided to start using the graphics of last year’s festival as the logo and we were looking for a designer who had poster design experience.

Sulev Salm advised us to talk to Enn Kivi who was the lead designer of Pärnu Fiesta. His style fitted our way of thinking and he was happy to come up with some witty designs for us. This is how the first pictorial poster was designed and since then, the poster has always had a certain image on it which usually includes swallows, the Moon and the Sun. The poster for the 1995 festival depicted a buxom lady sitting playing a zither on a boat.

The third festival included the first Instrument Fair where instrument makers and everyone else could sell and purchase new instruments, fix old ones or put their orders in with the craftsmen.

There have been so many memorable moments when organising the festival throughout the years that writing them all down would be impossible. That is why I will just pick out a few.

In 1996, I received my first big acknowledgement in the form of an annual Cultural Endowment of Estonia award. I also received the Viljandi Culture Award the same year. It is clear that these were not meant for me but for everyone who had helped to revive traditional music.

The line-up of the fourth festival included several stars such as Boys of the Lough and Garmarna. A year later, the Irish legend Deanta, my old idol Hedningarna and the Norwegian miracle man Knut Reiersrud gave a performance. Their arrival in Viljandi was a clear sign of quality and trust which opened up opportunities for us to cooperate with other Northern and Western European festivals.

In 1996, we added a new stage which was quickly embraced by the audiences – Kaevumägi stage at Viljandi Castle Hills.

In 1997, a folk music study camp for youngsters took place as part of Viljandi Folk Music Festival which was run by Krista Sildoja. Nowadays, it has become the Estonian ETHNO camp which has more than a hundred participants and carries the youthful spirit of traditional music while being a meeting and study place for many young traditional music fans.

In 1997, Mare Lilienthal, Liina Härm and Hillar Sein joined our team. These three have become an inseparable part of the festival and their advice and help have become irreplaceable. Mare’s first feat was creating a perfectly functioning volunteer employment system. Liina was a remarkably determined assistant who was for a long time responsible for the entire internal communication of the organisation. Hillar boldly developed the festival’s technical side.

Even though it might not seem like that from the outside, the development of the festival was not always plain sailing – organising the festival has been influenced by twists and turns in personal lives, families breaking up and many other unforeseen circumstances. For example, we had to turn a completely new leaf in our activities in 1997 when I went to the University of Tartu. There is no point in denying that the inadequate flow of information due to my absence caused a lot of tension within the organisation. In addition to that, the economic problems in 1997 created doubts and a feeling of uncertainty. Fortunately, the holy angel Ene Lukka came and helped us rearrange our lives.

Everything seemed to be going swimmingly. We received a respectable award again in 1998 – the annual Cultural Endowment of Estonia award. Viljandi City Council chose me to be the Person of the Year. At the same time, I realised that the festival needs a more secure organisation to run smoothly. We started preparing for a new organisation which would include the City of Viljandi, the Union of Viljandi County Municipalities and the Culture College and the aim of which would be solely to organise the Folk Music Festival. Up until that point, the festival had been organised by the Young Musicians’ Society which had grown into a civic society with quite a large following. The members of the society had different interests but the management only dealt with organising the festival which was unfair from the point of view of the organisation.

In the autumn of 1999, we hired our first full-time employee - Piret Aus became the Head of Programming. Her arrival was like the homecoming of a long lost son. She had founded a music school in her home area after graduating from the Culture Academy and had been running it up until the local government was forced to close it due to financial difficulties. Before joining the festival team, Piret had been working at the newspaper “Ruupor”.

Piret Aus was demanding, precise and thorough in everything she did. A few years later, she was the second person involved with the festival to receive the greatest acknowledgement of the City of Viljandi – the annual Viljandi Culture Award.

In 1999, we started preparing for founding a non-profit organisation which would concentrate solely on organising the festival. On January 1 the next year, NPO Viljandi Folk Music Festival was founded in collaboration between Viljandi City Council, the Union of Viljandi County Municipalities, Viljandi Culture College and several private citizens including Piret Aus, Liina Härm, Ülle Jantson, Ants Johanson, Ando Kiviberg, Marek Rätsep and Ene Talas.

The artistic level of the festival improved as the years went past and the festival became an international role model. In 2000, Viljandi Folk Music Festival became a member of the European Forum of the Worldwide Music Festivals. Despite that, we tried to avoid art becoming a goal on its own mind because traditional music is still mainly an art by the people.

The festival in 2000 was remarkable because the president of Estonia, Lennart Meri paid a visit which helped to boost the morale of the team. It probably helped that we devoted the festival to the great promoter of Estonian runo song, the composer Veljo Tormis who was celebrating his 70th birthday that year.

In 2001, the festival organisers started organising another festival in Tartu. In March, the first World and Wide festival took place. Before that, the president Lennart Meri gave me the 5th class Order of the White Star which again proved that we were doing the right thing.

Since the year 2002, we have been concentrating on one specific theme every year. For example, 2002 was the year of the zither and 2003 was devoted to singing. The theme of the festival in 2004 was “Whistles and Pipes”. In 2005, it concentrated on bowed instruments. We have been choosing our themes following these guidelines ever since.

In 2004, the Viljandi Folk Music Festival’s organisation team received the highest national award – the National Culture Award of Estonia. At the same time, the range of the organisation had grown which is why we decided to reorganise the non-profit and change its official name to Estonian Traditional Music Center. I who had ended up in Tallinn in the meantime, decided to give up my public sector job and started working full-time in the festival office.

In collaboration with Viljandi City Council, we started preparing for the reconstruction work on the old ruins of a granary at Kirsimägi to turn it into a home for the organisation and a concert hall. We had a lot of ambition and it was by no means an easy project. Despite all that, a miracle happened and with the help of several organisations and private individuals, we opened the Traditional Music Center in 2008. Now that the centre has been successfully working at the edge of the Castle Hills for several years, it seems as if the building had always been there because of how well it fits into the landscape and the concert hall scene in Estonia.

Viljandi Folk Music Festival has made impressive progress since its conception. The small traditional music party has become one of the largest music festivals in the Baltic and Nordic countries which attracts thousands of people every year. Our joint efforts have made Viljandi a household name at home and abroad. In addition to all the aforementioned awards and acknowledgements, the festival was also named the most successful tourism object or project in Southern Estonia one year which shows that the festival has given a boost to the tourism industry.

All in all, the most important thing is and always was reinvigorating and promoting Estonian traditional music. We want to inspire young people to sing their own songs, play their own tunes and dance their own dances to keep our traditional culture alive and kicking similarly to the mother tongue which we use to communicate with each other.

See you soon!